|

By G.K.Sharman Amid this pastoral backdrop, Betty O’Toole, clad in boots and jeans and a sweatshirt, walks to the end of a row of hopeful young potato plants and picks up a handful of soil. Dirt is good, and you have to get your hands in it, she tells the visitors following her around the herb farm that spring day. Her roots are deep in the sandy loam of Madison County, population 18,000 and change. She and her husband Jim, owners of O’Toole’s Herb Farm, grow plants much the way her ancestors must have, on land that has been in her family since the 1840s. It’s a safe bet that her forebears never grew shiita But for the O’Tooles and their fellow Florida organic farmers, the old methods are the future of agriculture. A certified organic herb nursery and garden, the O’Toole farm sells wholesale and retail herbal plants, fresh-cut herbs and greens and shiitake mushrooms. It’s one of nearly 130 certified organic operations in Florida, according to the Florida Organic Growers Association, said Juan C. Rodriguez, FOG’s director of education and outreach. And those are just the ones that FOG knows about and that are certified by Quality Certification Services in Gainesville, which is in turn certified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Organic refers to food that is grown, packed, processed and stored without the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides or irradiation. Proponents maintain that the food tastes better and is healthier for both consumers and the earth in which it’s grown.

Under Florida law, a product can be certified organic only if: -- No harmful chemicals have been applied to the land for at least three years. The penalty for claiming to be organic if you’re not isn’t chicken feed: a $10,000 fine. FOG doesn’t keep track of all of the organic producers out there. Operations with less than $5,000 in gross sales of organic goods don’t have to be certified, Rodriguez said, and other producers may be certified by other firms. Florida’s certified organic producers include farmers, livestock producers and food processors, and they stretch from Madison and other Panhandle communities south to Homestead. For a list of QCS-certified farms, ranches and processors, click here: www.qcsinfo.org/entities/QCS_Ent07.xls. In terms of volume, the largest organic crop in the state is citrus, followed by produce such as greens, lettuce, tomatoes and peppers. Other crops include everything from coffee to soy, grain to pecans and even tobacco. Cattle and chickens are raised by certified organic livestock producers and 16 processing plants turn out ready-for-market meat products and dog treats as well as such items as flour and barbecue sauce. Nationally, the organic industry in the United States grew 17 percent in 2005, the latest year for which figures were available, reaching total consumer

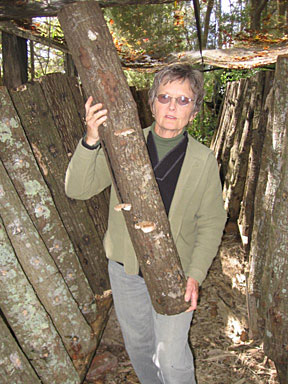

sales of $14.6 billion. The largest portion of the market is organic foods, which grew 16.2 percent and accounted for $13.8 billion of the total. Other segments of the market include personal care products, nutritional supplements, fiber, household cleaners, flowers and pet foods, among other items. Organic farming is practiced in approximately 120 countries throughout the world, though the U.S. lags in terms of acreage per person and other standards. And we do things differently - and bigger - here. Once dominated by small producers selling their wares at farmers’ markets, organic farming in the U.S. has become big business and high profile. Green products are on grocery shelves all over the country, including at super-retailer Wal-Mart. Seventy-three percent of conventional supermarkets stock organic items, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Corporate giants such as Archer Daniels Midland, Coca-Cola and General Mills have gotten into the act by buying organic companies. And the University of Florida recently began offering an organic-farming major - one of the first universities in the nation to do so. Organic purists believe the movement - and they do consider organic farming a movement, not just a way to make money - has gotten away from its roots. Letting the big boys play in this green sandbox has served mainly to commercialize what should be a grassroots endeavor and weaken national standards for how organic farming and processing should be conducted. The O’Toole farm, which is among 12,000 acres under organic cultivation in Florida, is big enough to make a profit and small enough to stay close to its ideals. And like many of its green brethren, it also welcomes visitors. On this particular spring day, Betty - who prefers to go by B - leads a tour for a small group of guests. After the mushroom section - a covered area housing racks of deciduous hardwood impregnated with shiitake spores - it’s on to the original garden.

The potatoes are here, as well as the greens and lettuces, the rows of mint and the arugula with its peppery, edible flowers. Farming organically isn’t harder than conventional farming, or more expensive, B said, but it is trickier. The technique relies more on lime and compost and know-how than on better living through chemistry. She and Jim started farming 17 years ago, she said, catching the knife-edge of the nation’s interest in organic foods. “We didn’t have any training in it,” she said,’ we just wanted to do it.” The goal was to produce better-tasting herbs and also to replenish and maintain the soil’s fertility and help keep nature in balance. Back then they figured they’d produce fresh-cut herbs for restaurants nearby and in Tallahassee, about 20 miles away. They were one of Florida’s first organic farms and interest in their product spread throughout the neighboring counties and across the Georgia border to Valdosta. Things have changed. The fresh-cut business is over, replaced by what she called “a huge market for plants,” especially for the wholesale market. The greenhouses cover as much area as the original garden and the client list stretches from Jacksonville to Destin and up to Valdosta and beyond. The drive to rural Madison is neither quick nor direct, yet “people would come all that distance to get a load of plants,” she said. The quality is what draws them, she believes, as well as the variety. In all, the farm grows 450 kinds of herbs and plants, including 12 kinds of basil and 10 varieties of mint. Individual plants are for sale too, and after learning how healthy they are for both humans and the environment, who could resist taking some home for their own garden. And don’t forget the large bag of, um, all-natural, animal-product fertilizer - after all, you wouldn’t use chemical fertilizers, would you?

|

<

ke mushrooms, though. And they probably had little use for basil or fennel or arugula. It’s also a safe bet that, though most of them farmed without chemical pesticides or fertilizers, they never called their operation organic.

ke mushrooms, though. And they probably had little use for basil or fennel or arugula. It’s also a safe bet that, though most of them farmed without chemical pesticides or fertilizers, they never called their operation organic.