|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Florida's

Black History

by

G. K. Sharman

February is Black History Month, when the nation remembers and

celebrates the contributions of its African-American citizens. Blacks

have been part of the Sunshine State since the peninsula was a swampy,

mosquito-infested outpost of the Spanish Crown.

You can read up on the full history in more complete sources. We'll hit a few of the highlights here.

Eatonville:

the first black town

The time was Reconstruction. The Civil War was over,

slavery was dead and blacks across the South were looking forward to prosperity

and a better way of life. Some started establishing homes and businesses

in white communities - which often led to friction between the two groups.

Rather than be shunted off to undesirable parts of town, many blacks

established independent communities known as "race colonies."

Such was Eatonville.

Who

is

|

A number of blacks lived in the white community of Maitland. In 1882, businessman Joseph C. Clarke bought some land from Maitland Mayor Josiah C. Eaton. Clarke began selling lots to black families from Maitland and nearby Orlando and Winter Park. By 1887, though race relations were relatively harmonious, many blacks dreamed of having their own town. On Aug. 15 of that year, 27 registered voters, all black men, met and voted to incorporate. The new town consisted of 112 acres (the land Clarke bought, plus a 10-acre donated tract) and was called Eatonville in honor of the original owner.

That vote made history: Eatonville was the first incorporated African-American community in the nation. Some 100 such communities were founded during the same era; only about a dozen remain.

Surrounded by ever-expanding Orlando and its surrounding communities, the town is perhaps best known these days for its annual showcase of arts, literature and culture that celebrates native daughter Zora Neale Hurston (www.zoranealshurstonfestival.com).

The most recent event, held in late January, drew some 160,000 people

to the tiny metropolis and attracted such big-name talent as salsa legend

Celia Cruz, the Ramsey Lewis Trio and gospel storyteller and evangelist

Dorothy Norwood, who once opened for the Rolling Stones.

The event also included education and fun events for some 10,000 to 15,000

youngsters; forums on jazz, theater and film presentations; and a street

festival that included live music, a writers' pavilion, a juried art exhibit

and demonstrations of traditional crafts, as well as vendors and a variety

of food merchants. There was also an information booth to raise awareness on accredited online colleges.

The town also boasts the small but soon-to-expand Zora Neale Hurston National Museum of Fine Arts. This year's program consists of six exhibitions devoted largely to African-American artists.

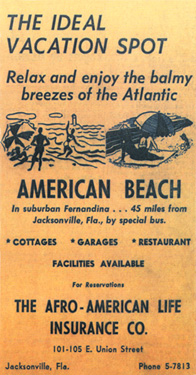

Black millionare- philanthrpist A.L. Lewis, president of the African American Life Insurance Co. in Jacksonville, created a place where his employees could enjoy what he termed "relaxation without humiliation." |

Other

significant sites & events

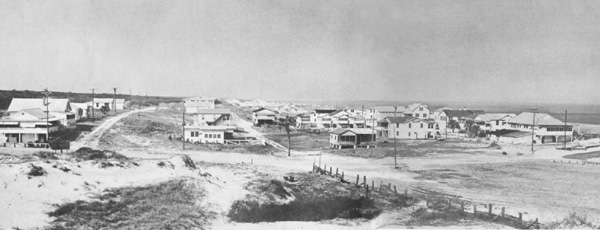

American Beach: Back in 1930, A.L. Lewis, president

of the African American Life Insurance Co. in Jacksonville, was looking

for a place where his employees could enjoy what he termed "relaxation

without humiliation." So he bought 200 acres on a strip of beach

northeast of downtown and began American Beach.

It was THE beach resort for African Americans until around 1970 and attracted visitors from all levels of society.

These days, MaVene Betch, Lewis' great-granddaughter, is the town's unofficial mayor. The town is about half the size it used to be, in part because of pressure from surrounding land developers.

Fort

Mose

Back during Florida's Colonial era, blacks fleeing enslavement

in Charles Town - later Charleston, S.C. - came south to St. Augustine.

In 1738, the territory's governor, Manuel Montiano, gave them sanctuary

and granted land two miles north of St. Augustine for a settlement. Thus

sanctioned by the government, Fort Mose (pronounced Mo-ZAY) became the

first legal, free African community in what later became the United States.

There was a catch, of course: the new Floridians had to pledge "to

shed their last drop in blood in defense of the Spanish Crown." About

20 families - some 100 people in all - lived there.

Africans were already a substantial presence in the St. Augustine area. The city, founded in 1565 by Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles, is the nation's oldest European city. Blacks, both slave and free, helped form and maintain the settlement. About 12 percent of the population was black; of those, about one in five was free.

American Beach cosisted of 200 acres of oceanfront property near Amelia island. It is now threatened by encroaching development. |

Gen. James Oglethorpe of the Georgia colony attacked the settlement in 1740. Soldiers from St. Augustine and Fort Mose fought together and, with help from troops from Havana and the threat of hurricanes, successfully defended the area.

Most of Fort Mose was destroyed, however, and most residents moved to St. Augustine. A second Fort Mose was built and occupied until 1763 when its residents, along with other Spanish colonists, relocated to Cuba.

Today the area that was Fort Mose is a National Historic Landmark.

Battle

of Olustee

Remember the movie "Glory," which recounted the exploits of

the 54th Massachusetts Infantry? The 54th was one of the first black units

organized in the northern states during the Civil War. By 1864 the unit

was a battle-hardened force to be reckoned with, as well as a household

name because of what happened at Battery Waggner in the summer of 1863

(no, you'll have to rent the movie to find out).

In February 1864, it was part of the Union force that tangled with Confederates at Olustee (also called Ocean Pond) in the largest Civil War battle in Florida (http://extlab1.entnem.ufl.edu/olustee/).

Visionary Mary McLeod Bethune started Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona beach as a school for black girls. |

The two sides fought nearly all day and by nightfall, the union was in retreat. The 54th, along with another black unit, the 35th U.S. Colored Troops, joined the fighting late in the day and helped save Union troops from disaster.

The battle is re-enacted every February at the Olustee battlefield Historic Site (in Baker County, west of Jacksonville on I-10). This year's dates are Feb. 15-17.

Education

Bethune-Cookman College and Florida A&M University are

historically black institutions of higher learning. B-CC in Daytona Beach

began in 1904 as a school for black girls under the leadership of a dynamo

named Mary McLeod Bethune. The school gradually evolved and the state

OK'd a four-year liberal arts and teaching program in 1941.

Today B-CC offers degrees in 39 subjects. For the 1999-2000 academic year, it awarded degrees to 268 students.

Florida A&M University - which stands for Agricultural and Mechanical - was chartered in Tallahassee in October 1887 as the State Normal College for Colored Students. In the 1950s and '60s, it became the first black institution to be accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and School.

In 1984, the two schools sponsored a spring break gathering of students and alumni in Daytona Beach. The event grew into Black College Reunion, the largest event in the nation to target black college students and alumni. It's a weekend of concerts, festivals, competitions and fun in the sun - with an economic impact of $50 million.

Some 150,000 participants are expected this year, April 12-14 (www.blackfloridian.com).

New vision: R. Donahue Peebles, developed the first black-owned luxury hotel in the country. |

New History: Black Luxury Hotel

If all this history has you longing for a vacation, the Royal Palm Crowne Plaza may be the place to escape to. The $84 million, Art Deco facility on Miami's trendy South Beach will be the nation's first black-owned luxury hotel when it opens this month. The NAACP has already booked the place for its 2003 conference.

Spearheaded by real estate developer R. Donahue Peebles, the 422-room hotel plans to target groups and leisure travelers from the Northeast. Those travelers account for a good percentage of the $36 million African-American tourism market.

They'd better bring their platinum cards. Rates start around $200 a night for rooms, with beachfront cabanas fetching $550 in the summer and $659 per night during peak season.

Photo credits: R. Donahue Peebles photo, left and in collage above, Marcia Halper of the Miami Herald; Mary McLeod Bethune photo courtesy of Bethune-Cookman College ; American Beach photos, A.L. Lewis and MaVene Betch photos courtesy of AnAmericanBeach.com ; Zora Neale Hurston photo courtesy of http://i.am/zora . Collage by Barbara Bose.